Tideland

In 1998, while writing for UCLA's student newspaper The Daily Bruin, I attended an advance critics' screening of Terry Gilliam's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. The film did not go over well. Several VIP guests left during the show. My fellow reviewers, scheduled to interview Gilliam and stars Johnny Depp and Benicio del Toro the next day, shifted around in their seats and checked their watches and generally made their impatience known. I enjoyed it more than the rest, but like everyone else, I found the film a convoluted, even frustrating experience. And I'd read the Hunter Thompson novel on which it was based. It took four or five more viewings, theatrically and on DVD, before I truly appreciated the scope and intelligence of Gilliam's adaptation.

Gilliam's style, at this point, has become deliberately disorienting. He fills shots with clutter and busy, tangential motion. He shoots from odd, imprecise angles. His actors mutter over one another and drift off, making it extremely difficult or impossible to follow conversations. In Fear and Loathing, he used this technique to capture the anarchic, unrestrained nature of Raoul Duke and Dr. Gonzo's drug abuse. Of course you'd see rooms spinning and filled with alcoholic lizards if you're only perspective is provided by a guy sniffing ether off of an American flag.

Gilliam takes an even more chaotic approach with Tideland, a dark twist on the children's fantasy adventure in which no sane, objective reality exists. Gilliam's adaptation of Mitch Cullin's novel borrows heavily from Lewis Carroll's Wonderland stories but with one crucial difference. Alice begins her journey in our world, studying in the park, before she wanders off in pursuit of a White Rabbit. Jeliza-Rose (Jodelle Ferland), the unfortunate orphan at the center of Tideland, starts off the film already insane and living amidst ranting madmen. If this is a play on the Wonderland story, she's not the Alice character. We in the audience are Alice's stand-ins, curious visitors from the Outside. Jeliza's just another freak in the freak kingdom.

Making a film that exists in an irrational universe without any sane characters provides for some unique complications. The story of Tideland, such as it is, has absolutely no narrative momentum. There is no beginning, middle and end. Situations unfold and then resolve themselves. Or maybe they don't. And nothing has any sort of real impact on any of the characters, good or bad, because they are all living in strange, imaginary lands of their own creation where actions have no consequences and events have no meaning. The movie is occasionally exciting, always beautiful and sometimes intriguing, but not really all that entertaining. Those of us still in command of our mental faculties may look for something more concrete to hold on to than a 2 hour story about talking doll heads and squirrel hunting.

Jeliza-Rose lives in urban squalor with her junkie parents. She spends her days preparing needles for her rock musician father (Jeff Bridges) and chain-smoking, pregnant mother (Jennifer Tilly), then indulging in her complex, melodramatic fantasy life once they've passed out. Though she's clearly the most together, rational member of Tideland's cast of merry whackjobs, Jeliza-Rose may in fact be schizophrenic, providing voices for a series of bodiless Barbie heads in the service of looping, inane conversations.

When Mom O.D.'s, father and daughter hit the road bound for the prairie, where Noah's deceased mother owned a dilapidated house. With Dad distracted by heroin and, eventually, his own death, Jeliza-Rose befriends the creepy beekeeper Dell (Janet McTeer) and her slow, epileptic brother Dickens (Brendan Fletcher). United as a dysfunctional family unit, they all begin to creep deeper into madness.

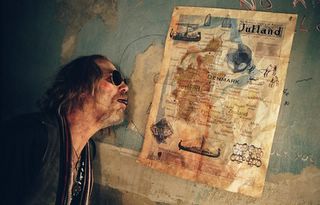

Gilliam's films have always been about the collision of dreams and reality. With Tideland, however, I think it's safe to say that reality has ceased to concern him. Nothing in the film feels possible, even the introductory material with Noah and Jeliza-Rose arriving in the countryside. Single houses plopped down in the middle of wheat fields? Overturned, burned-out school buses set next to railroad tracks leading nowhere? How do they all find food? Where do they get fresh water? It's as if the entire film were one of Noah's drug-induced fantasies, like his planned camping trip to the Danish Jutland as an escape from the responsibilities of adult life.

Rather than the friction between the imaginary and the real, Gilliam here explores the tension between innocence and decay. No matter how hard Jeliza-Rose tries to shut it out, death lingers behind her every thought and every delusion. It dawns on her very slowly that dress-up games and good cheer aren't enough to cheat nature's laws, no matter how much you believe they can.

It's here, I suppose, that the constant literary references come into play, though they still come off as unnecessary and forced. The power of the imagery in Tideland is more than enough to Gilliam's ideas about a child's ability to process trauma. (One shot that sticks in my mind is Jeliza-Rose's house sinking like a ship beneath an ocean of brown wheat.)

He doesn't need to keep referring back to not only "Alice in Wonderland" but the entire Western canon of beloved children's literature. As in his last effort, career-low The Brothers Grimm, Gilliam falls back on "references" and obvious allusions far too often. In that film, it was little nods to dozens of fairy tales, and here it's more about classic books and bedtime stories, but the effect is the same.

McTeer's Dell, the film's lone "villain," recalls at different times The Wicked Witch of the West, Captain Hook and Miss Havisham from "Great Expectations." (Granted, not usually listed as a children's book, but consider that her brother is named "Dickens.") When we meet her, she's quoting Carroll's Caterpillar - "I say what I mean is not the same thing as I mean what I say." Other sequences borrow ideas from C.S. Lewis, Roald Dahl and Pinocchio. I'm sure there were some sidelong references that I missed, too, because the entire film feels informed by these famous novels, myths and fables.

As in all of those stories, Jeliza-Rose sees the worst and darkest of nature and humanity through a child's eyes. Not only the death of her mother (and soon after, her father), but all manner of corruption and depravity. She witnesses the aforementioned drug abuse as well as child abuse, neglect, starvation, homicidal impulses, jealousy, greed, the destructive force of nature, incest, child molestation and intense, searing loneliness and spins all these experiences into a deeply personal, twisted mythology. She lives with her father's rotting corpse and turns it into a game.

Gilliam co-wrote the screenplay with his Fear and Loathing partner Tony Grisoni and the result is the same mesh of light and dark sensibilities. Deadly serious material infused with comedy but also a sense of frivolity, as if even the most horrifying traumas will eventually fade away and disappear into the past. Nicola Pecorini, another Fear and Loathing vet, plays similar tricks with lenses and lighting to distort the imagery and confound the viewer.

Overall, it's an interesting experience but not necessarily a captivating film. I found my attention wandering frequently. His most entertaining films feature characters with warped perspectives, much like Tideland, but we're generally granted access to the character's insanity. In 12 Monkeys, Cole's time travel makes him seem crazy to psychiatrists, but we know what he's talking about, because we've seen his grim underground future world.

Tideland puts the viewer in a fairly sensible place - a large wheat field - and then fills it with absolute loons with whom it's impossible to relate. We recognize the dismal horror of their lives, and their peculiar deviations from the norm, but they don't grant us any access to their inner lives. Jeliza-Rose remains completely enigmatic from the first shot to the last. What is she thinking, drifting around this empty house, listening to the flies and ants pick at her father's decaying body? Is she thinking, maybe, she should try to find a phone and call Protective Services? Or was that just me?

No comments:

Post a Comment