Bugsy

The entire time I was watching Bugsy, I kept remembering Martin Scorsese's The Aviator from last year. The films take place within 10 years of one another, with Aviator opening in the 30's and Bugsy in the 40's. They are both autobiographies of notorious dreamers; Scorsese's film takes on the remarkably ambitious yet mentally ill Howard Hughes, while Barry Levinson's Bugsy looks at ambitious yet neurotic gangland figure Benjamin Siegel (Bugsy to the press). They were both outsiders who fell in love with the style, glamour and women of Hollywood.

But beyond these surface details, the films share a fealty for the past, a desire to create not just a portrait of a memorable historical figure, but a panorama of this period in American history. Both succeed on some level, though I'd say Aviator is by far the greater film, more heartfelt, more nuanced, more imaginative, and far more cinematic. Bugsy doesn't so much envelop the viewer into the fully-realized world of period Hollywood the way Scorsese does, but the film does get a lot of the details right, and it does tell a fairly remarkable true story.

All the famous gangster names from the 40's kind of get jumbled together, and people don't really remember what each individual guy was known for. There's Mickey Cohen, Meyer Lansky, Bugsy Siegel, Bugsy Malone, Legs Diamond, Dutch Schultz, Lucky Luciano...and a whole shitload more. Lots of contemporary films have tried to reenact their struggles for power and the inner-workings of their relationship, but it tends to become overwhelming, complex and unsatisfying. Remember Mobsters? Or Hoodlum?

Bugsy screenwriter James Toback instead focuses on just the Benny Siegel story (though it involves Lansky, Cohen, Luciano and other notable figures from the criminal underground fo the time). This makes sense, both because star Warren Beatty had worked to get a film made about Bugsy for many years, but also because of Toback's career-long fascination with gamblers.

At its heart, that's what Bugsy is all about. A man so obsessed with gambling that he continually and pathologically put everything in his life at risk. Meyer Lansky (played in the film's best performance by Ben Kingsley) says about his childhood friend that "Benny never cared for money," and we come to see that this is true. Money is merely the means to an end; it is useful only in that it can be sacrificed in the realization of some grander vision.

For a businessman like Lansky, money is the end point, the final result of a lifetime of hard work. But for Siegel, it exists only to provide him with attractive women, respect, fame and power.

The film focuses on two significant events in Siegel's life. The first is his meeting Virginia Hill (Annette Bening) while hanging out on a movie set with his friend, actor George Raft (Joe Mantegna, who oddly doesn't look or sound anything like the real George Raft). Though Siegel's married with two children at the time, he will eventually leave his family for Hill, the love of his life. The second is his visit to a small bar/casino owned by Meyer Lansky in the Nevada desert.

Famously, Beatty and Bening actually fell in love during the filming of this movie, and their real story kind of echoes the one they're acting out. An older womanizer meets a striking younger beauty on a film set and falls in love with her. So it's strange that the romance never really comes alive on screen.

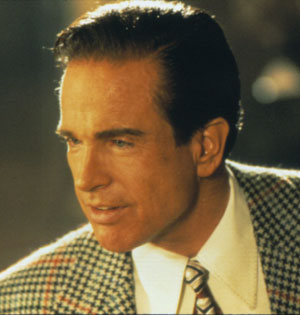

He's a terrific actor and I don't want to fade him because once he was very nice to me, but Warren Beatty is kind of the problem here. In the scenes focusing on Siegel's raw ambition, Beatty is great, adapting a kind of fast-talking, shifty demeanor that's kind of different from any other performance of his that comes to mind. But he seems kind of distracted during the scenes with Bening. The plot turns on Siegel's complete devotion to Hill, but when they're together in the film, he doesn't ever even seem that into her.

Late in the film, LA gang leader Mickey Cohen (Harvey Keitel) warns Benny that Virginia may be stealing from him. Benny reacts angrily, violently, denying that it could ever be possible. It's the first time we've seen him express his love for Virginia emotionally. Unfortunately, by that point, the relationship has been established and the plot's final movements have already been set into place.

That scene, though, brings up the other real shortcoming in the Beatty performance. Bugsy Siegel had a massive temper, and there are several points in the film in which he's called upon to explode in rage or even violently attack someone. Beatty never convinces us of this man's internal struggle with anger or that he would ever be an imposing threat to those around him. Maybe it's that Warren's a few years older than anyone else in the principal cast, or maybe it's that he tends to play reserved, thoughtful guys rather than mad dogs. But whatever the reason, his attempts to portray Siegel's sociopathic criminal tendencies aren't believable, and even get a bit silly at times.

Considering his emotional attachment to this material, it's surprising Beatty didn't simply direct the film himself, rather than turning over the reigns to Barry Levinson. I like Levinson, he's made some good films (Tin Men being a particular favorite of mine) and he does a nice job. The film has a really old-fashioned kind of visual style that's obviously appropriate to the material, and the realization of 40's Union Station in LA or of the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas upon its initial opening is handled really well.

But the whole thing's a touch obvious, a bit clear from the beginning. I mean, obviously, the film is based on true historical events, so you can't fudge the truth to make it more surprising at the end. But there's this feeling of inevitability over the proceedings that I didn't really care for.

An example: there's a whole sequence, set in Cuba, in which Lansky, Luciano and other gang leaders from America discuss the Bugsy situation and how to handle it. We're tipped off at this point that they all basically want Bugsy dead, and that his friendship with Meyer is the only thing keeping him alive.

It's a nice scene, and of course it's fun to see all of these notorious, iconic figures in such a setting, but it also kills the momentum of the film's final act. Most regrettably, Toback then provides Kingsley with a silly monologue that essentially explains the theme of the movie to the audience. "Benny's a dreamer. He didn't care about money. He wanted to build something that would last." And on and on.

But even before that, the movie insists on foreshadowing Benny's fate constantly, and nothing makes a film feel flat more than constant telescoping, setting up exactly what's to come. It makes the entire experience of film-viewing feel rote. Films, particularly crime films, should never feel this obvious, whether or not you already know the story going in.

Like its subject, the film Bugsy is kind of a dreamer. It hopes to be a searing American epic, a romantic biography of an iconic figure told in big, bold strokes. It never quite gets there. But it's nice to see a movie with oversized ideas anyway, I suppose, even if it's not The Aviator every time.

No comments:

Post a Comment