Pickpocket

Robert Bresson's Pickpocket, a really haunting portrait of self-loathing and criminality from 1959, actually came out on DVD a few weeks ago. But for whatever reason (most likely forgetfulness), I never got around to actually writing up a review. But I couldn't let the occasion of the film's release on a pristine Criterion DVD just pass without saying anything.

That's amateur Martin LaSalle as Michel, the titular pickpocket, who steals out of financial desperation as well as an egomaniacal sense of entitlement. French director Bresson always made use of non-professional actors, and would famously force his actors to perform a scene repeatedly, until all emotion and meaning was drained out of the performances. He wanted blank slates, canvases onto which an audience could project their own fears, dreams, desires and neuroses.

Michel initially picks pockets for the rush, and as a personal challenge - he wants to see if he can get away with something illegal and immoral. When he does, and suffers no consequences, he soon becomes a professional, learning a great deal from veteran pickpocket Jacques (Pierre Leymarie).

In terms of narrative, the film is pretty similar to Dostoyevsky's novel "Crime and Punishment", only without the axe murder stuff. Michel makes what he sees as a rational argument for his pickpocketing (as a great intellectual and thinker, he shouldn't be forced to work for a living in some pointless job), and is eventually won over to the side of right not by reason but by the love of a good woman. In this case, it's Jeanne (Marika Green), the sensitive nieghbor of Michel's sick mother who loves him without question.

It sounds heavy, but it's not at all. The film is fast, brief and even exciting. The sequences in which teams of pickpockets descend on crowds in the subway, where Bresson's camera follows just their fast-moving hands pulling wallets and flitting them around, are like a masterclass in cinematography. Bresson captures the devious, deceptive nature of the pickpocket's movements, constantly shifting your attention away from the actual moment of theft.

And it all wraps up in one of the most beautiful, haunting final scenes in motion picture history. The last line has become a classic for international film fans, and it's only in the movie's last moment that you can truly appreciate Bresson's vision and humanity.

As a bonus, the disc includes an interview with writer/director Paul Schrader, in which he discusses Bresson's technique and influence, and a really cool clip from French TV by Pierre Leymarie (a real-life magician and pickpocket who acted in and consulted on the Bresson film).

Forbidden Games

Another brief 50's French film that packs a big emotional wallop. (Pickpocket is 75 minutes long, Forbidden Games a slightly longer 85 minutes). Rene Clement's wartime drama features two of the best child performances I have ever seen, from 5 year old Brigitte Fossey and 12 year old Georges Poujouly.

As the film opens, Paulette's parents and beloved pet dog, Jock, die after a German bombing. She finds her way to the Dolle farm, where young son Michel (Poujouly) finds her and bonds with her immediately. She comes to live with the family, passing time playing with Michel and obsessing about giving her dog a proper burial.

This is a strange film. For the most part, it's carefully observant about the way not just children but all people deal with death. They become obsessed with little details, with the notion of greiving, and with the idea that proper treatment and care, a dead person's soul can be brought to a place of peace and serenity. For Paulette, she insists that Michel build her a pet cemetary in an old mill, not just for Jock but for all animals in the area who have died. A plan to steal crosses from the actual cemetary to mark these graves is the incident that triggers the film's narrative.

But on another level, Clement sees the war as the ultimate disruption to French society and life. The opening scenes, of planes dive-bombing while families run for dear life below, reflect the tone of the entire film - a world gone mad, in which everyone is a constant target for violence, and death lurks around each corner. There isn't a scene of this film without some sort of death imagery, whether it's an owl hiding a dead mole in its nest or a family member receiving a fatal kick from an escaped war horse.

Nothing is stable, everyone is affected, and the only meaning any of this chaos has is what meaning people choose to give it. Just like Paulette and Michel's "play cemetary," there's a notion that the adults, building decorated hearses and reciting the Lord's Prayer, are merely engaging in their own form of make-believe.

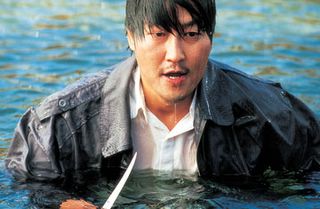

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance

From France in the 50's, we turn to Korea...a few years ago. This film is the first in Chan Wook-Park's Revenge Trilogy. (It's only a thematic trilogy...The movie's have nothing aside from subject matter in common.) Volume Two was the mesmerizing Oldboy, which I reviewed here with breathless enthusiasm. Volume Three, Sympathy for Lady Vengeance, comes to America (hopefully) in 2006.

Both Mr. Vengeance and Oldboy feature parallel revenge stories; multiple characters, each motivated by a desire to repay a perceived gross injustice. In Oldboy, a man is imprisoned for 15 years in a motel room, and then sets out to find and kill the man responsible. In an increasingly disorienting odyssey of discovery, he learns that his imprisonment was itself revenge for an earlier crime against his jailer.

In Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, a deaf mute named Ryu (Ha-Kyun Shin) makes a deal for a black-market kidney. In exchange for an organ to match his ailing sister's blood type, he hands over not only money, but one of his own kidneys. Upon waking from the operation, he discovers the organ dealers are gone, with his money and kidney. Now, when a real donor kidney appears, he's forced to kidnap the child of a wealthy businessman (Kang-ho Song) in order to get back the money, to pay for the operation.

Naturally, the kidnapping goes awry. There are several deaths, and the businessman and mute are set on parallel revenge stories, each after the person they see as ultimately responsible for all the destruction and tragedy.

So both films deal with the inevitably unsatisfying nature of vengeance. What begins as a quest to punish others for past wrongs always turns obsessive and ultimately pointless. To kill a man is not curative; violence begets violence.

But this is where the similarities end. Oldboy is like a jolt to the system, a 2 hour theme park ride full of turnabouts, stylistic leaps, brilliant effects sequences, rapid-fire editing and action sequences. Though it's built around a "twist ending," the entire film is really one big mindfuck. Your perspective on events is continually skewed, your understanding of motivations upended.

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, though equally violent in spurts, is altogether more meditative, quiet and reflective. Having a main character who's unable to speak gives Park the opportunity to focus more on visual storytelling, and even the "action" sequences move more languidly than Oldboy. If that film makes revenge appear as a chaotic nightmare of unexpected consequences, here it's a harrowing, grim march to inevitable tragedy.

Park as well infuses his twin revenge films with very different subtexts. In Oldboy, the revenge cycles around deviant sexuality. Oh Dae-Su's imprisonment, his ironic punishment and everything in between are circumstances fueled by shame. His foe doesn't want to hurt him for anything like money, or in fact, any rational reasons at all. It's a matter of personal pride, the last attempt for an unbalanced man to "set the world right."

But in Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance, all of the exchanges are monetary. Ryu needs money for his sister's operation, and he chooses a target based on his wealth. In both cases, the revenge follows a broken contractual agreement. The organ donors promise a kidney and don't deliver. Ryu promises a child in exchange for a ransom, and doesn't deliver. When these negotiations break down, the parties involved turn primal, seeking their retribution through any means neccessary.

By the end, when the two men finally have their face-off, neither of them even seem angry. It's more out of a sense of ritual, or duty, that the final act of violence takes place. "You know why I have to kill you," the businessman says, with a look of utter defeat. He doesn't relsih sweet revenge, but undertakes a dirty chore out of loyalty to his dead offspring, on behalf of wronged parents the world over.