A young man struggling to earn any money he can be taking on odd jobs, Sébastien (George Babluani) finds himself in the employ of a heroin-addled old man. While he's fixing the guy's roof, he overhears some strange conversations. There's an envelope coming in the mail. It will include a ticket. The old man is to take a train to Paris and await further instructions. Whatever this strange assignment is, it will pay handsomely.

When the junkie dies suddenly (as junkies occasionally do), Sébastien takes his place, hoping for a big payday to help support his needy family. What he finds at the other end of that ticket is a degrading experience of horror and subjugation in which his misery will provide entertainment for a cabal of old rich men. I don't want to reveal any of the gruesome secrets Babluani has in store, but comparisons to Eli Roth's Hostel are not totally unwarranted.

Babluani makes some key choices that ratchet up the film's suspense factor considerably. The stark black and white cinematography, heavy on elongated intimate takes and close-ups, always pulls away at the last second before things get really gory. But it constantly threatens not to, as if Babluani's teasing the viewer. Will I remember to look away this time, or force you to bear witness to the grisly aftermath of this violent act. (Repeated inserts of a light bulb going on and off become almost unbearable by the film's end).

Likewise, the decision to go almost entirely without a score adds considerably to the final impact. Sequences of extreme emotional intensity, which generally would be accompanied by a swelling crescendo on the soundtrack, pass by in eerie silence. Gun shots, in particular, reverberate with greater emphasis because of the film's still, quiet atmosphere.

The concise directness of Babluani's film eventually works in his favor. This is not a complex story. Sébastien goes on a mysterious quest and things go extremely awry. He finds himself accidentally plunged into a very real nightmare from which there seems to be no hope of escape. From that point, things pretty much unfold as expected, albeit with some highly effective sequecnes of suspense along the way.

I suppose it's not really a complaint, as I kind of admired the single-mindedness with which Babluani approaches the thriller genre, but still...there's a strong classist/Marxist bent to the material that I would have liked to see explored a bit more. Like Eli Roth's Hostel, Tzameti eventually finds its way around to an allegorical critique of capitalism. (I hope I'm not giving too much away.)

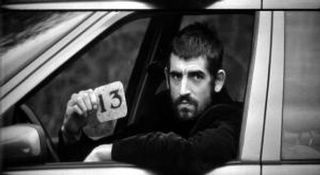

Money is thrown at Sébastien and he becomes little more than a pawn, assigned a number and enlisted into the forcible service of a rich, powerful and unconcerned older man. The kind of financial desperation he faces at the film's opening is the ideal set-up for exploitation - he can be bought, and cheaply, because the only other option is homelessness and starvation. (A brief scene in which he's informed he won't be paid for the work he has already done on the roof captures the despair of the bankrupt with remarkable efficiency.)

As in Roth's film, the notion of human beings as chattle comes up repeatedly in Tzameti. These people are paid to do a job and essentially cease to be human begins. They transform into property, to be traded and bartered over, to be bought and sold. Babluani seems to see this metamorphasis as an essential facet of the modern world, intrinsic within human nature. By the end of his film, the exploited themselves have even adopted this ideology. They bring these attitudes along with them even after their service comes to an end. Second-class citizenry, then, is not just about being subjugated, but also indoctrinated, convinced that your station in life is permanent and self-defining.

Babluani extends the capitalist metaphor in some interesting ways. Sébastien's captors, who compel him into service through the threat of violence, seem indignant that he is not more thankful for their generosity. One even expects to be tipped afterwards for his efforts. Also notable is that other participants besides Sébastien has consented to take part in the project, desiring the chance at a fortune above their own safety. Babluani favors striking portraits shot in tight close-ups, studying the weary contours of the unfotunate' faces in harsh lighting and extreme angles reminiscent of the silent films of Dreyer.

Tzameti could develop some of these ideas a bit more. It takes too long to get going, spending a lot of time on the roofing job and the residents of the junkie's house for no good reason. Likewise, a 15 minute or so coda leads to an unfortunately predictable and unsatisfying conclusion. (There's only a few ways the film could possibly end). Roth, through his use of brothel/torture chamber metaphors, managed to fill Hostel with some interesting ideas about the nature of prostitution and exploitation in addition to the blood and guts. Tzameti, likewise, seems to have insights beyond its clever, twisting narrative. They just tend to get lost along the way as the focus remains squarely on ratching up the intensity and suspense. Still, this is bound to be one of the year's best and most promising debut films.

No comments:

Post a Comment